Network security will always be more important than ever before.

This statement will remain true regardless of when this topic is discussed. Security is consistently being tested; whether it be voluntarily via hired penetration testing, or not so voluntarily by bad actors, or “BADDIES” herein.

Those of us who are trusted to implement and administer infrastructure would be wise to never remain complacent with our security policies. What worked yesteryear may not be sufficient in future landscapes of increasingly evil ransomware/malware attacks. That being said there are still some proven methods that we can utilize to help mitigate some vulnerabilities.

In a previous post Dan dove into internal network access control, so here I’ll focus on a simple edge security tactic to help mitigate brute force password attacks on our VPN concentrators.

Side thought…

These types of attacks should hopefully never prove successful for the script kiddies behind them. However, given the disparity between password policies from one environment to another this may not always be true… but that’s a whole other topic, and an opinionated one at that.

Onto the example… a preventative measure we can take for this scenario is something I like to call “FOH BADDIES“, or more professionally, null-routing bad actors. We implement a policy-based null-route for specific traffic on our edge router which would prevent the authentication attempt from ever reaching our VPN concentrator in the first place… the specific nefarious traffic from a bad actor would be sent off into the nether.

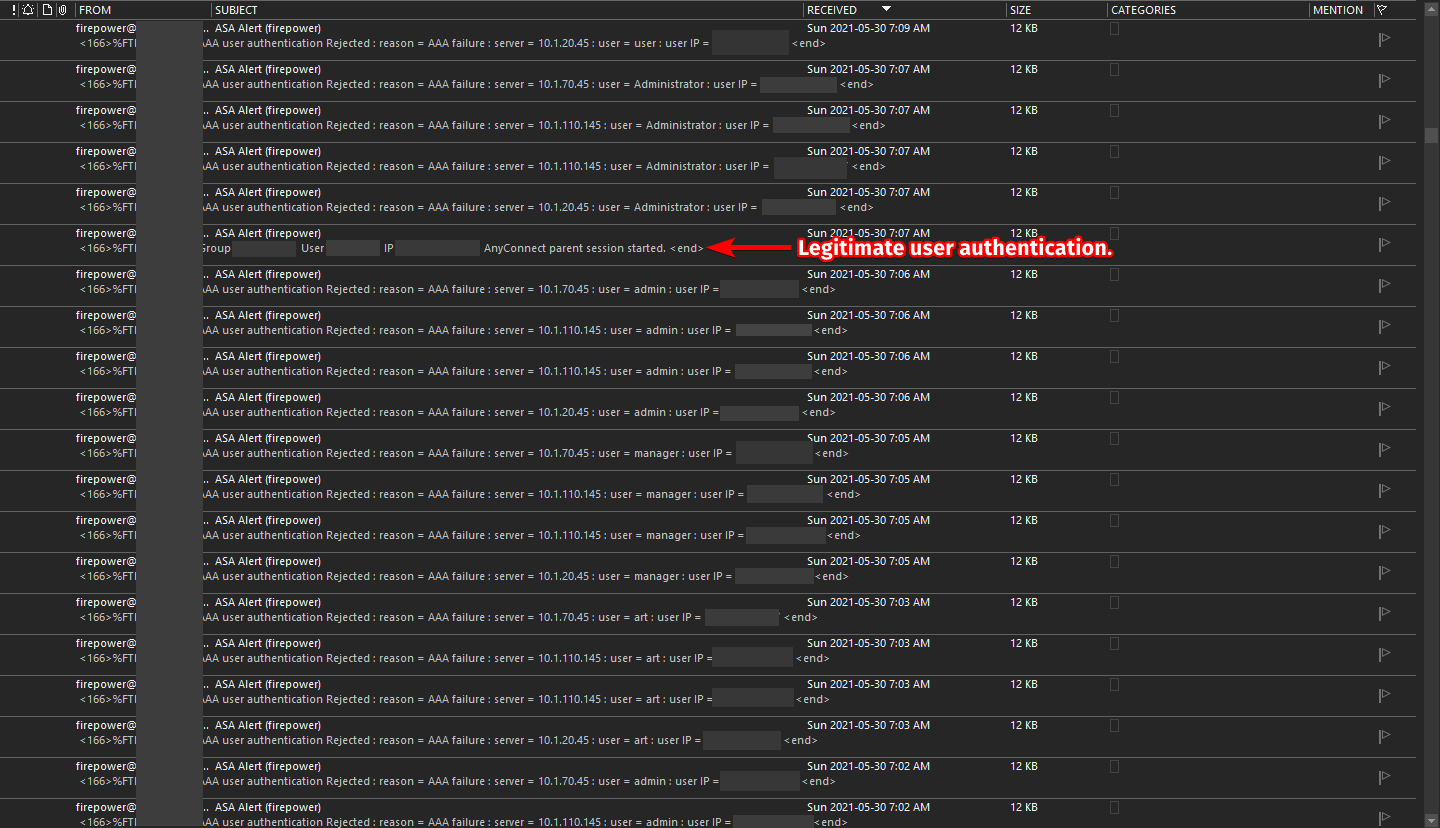

Since it’s a given that we’re all already logging VPN access attempts one way or another (you are, right?), it’s easy enough for us to spot a classic dictionary attack against our VPN policies.

Here we’re seeing a single page of many email notifications showing that a specific IP is attempting a very clear brute force password attack against our VPN concentrator; only one of those emails shows a successful legitimate user connection. Let’s pretend bad actor’s IP address here is “1.2.3.4“… to be honest, I struggled with whether or not to disclose the actual address used in these attacks, but opted not to out of an over-abundance of caution.

The meat n’ potatoes…

On our edge router we’ll create a standard access-list named “BADDIES” that contains a list of our bad actor IP addresses/subnets.

ip access-list standard BADDIES

permit 1.2.3.4 255.255.255.255

We’ll then create a route-map named “FOH” stating that any traffic matching the addresses/subnets found in the “BADDIES” access-list should be set to exit the router on the “Null0” interface (which is effectively a black-hole).

route-map FOH permit 10

match ip address BADDIES

set interface Null0

To prevent bad actors from detecting that you’re black-holing their traffic, disable ip unreachable messages from being generated on the “Null0” interface.

interface Null0

no ip unreachables

Then we’ll assign a policy-based route using the “FOH” route-map for this traffic.

Note: For this example, our edge router has a port-channel (1) to our edge switch, and our external transit subnet to our provider lives in vlan-300.

interface port-channel1.300

description ISP-CIRCUIT

encapsulation dot1Q 300

ip address 5.6.7.11 255.255.255.248

ip policy route-map FOH

With this configuration any traffic from “1.2.3.4” will be routed out the “Null0” interface, never to be seen again. If more bad actor IP addresses, or even subnets, are discovered they can simply be added to the “BADDIES” access-list.

Of course, this is a reactionary measure as bad actors can come from any IP address in any region at any time, so you’ll have to add them to the ACL as they come in; but I don’t suppose it would prove too challenging to automate this process with a python script, if one was so inclined… maybe we’ll head down that path in a future article.